Accessories, Cargo Terminals, Freight Forwarders, CARE, Ground Handlers, Regulators, Safety

Straps 2016: A New Era

Air cargo straps, aka cargo straps,tie down straps or just plain straps are probably one of the most misunderstood components of the air cargo industry, whether found on a built-up pallet load, or in a pile in the corner of the cargo shed, or adorning a freight forwarders truck. There are an amazing amount of these straps in existence combined with an amazingly small amount of knowledge about their proper use – this is not a formula for air cargo safety.

Like many other practices in the air cargo industry, the use of straps has evolved over time. Yes there has been a certain amount of instruction in the use of straps contained both in the IATA ULD Regulations and in its predecessor, the ULD Technical Manual, basically reproducing the contents of ISO 16049. A certain amount of guidance can also be found in the IATA AHM but there is a bigger issue here which is that from the very beginning of palletized cargo, the weight and balance manuals were created on the assumption that the primary restraint would always be a cargo net and that if and when straps were to be used, they would always be a secondary restraint, underneath the cargo net. The FAA is very clear about this: the use of a pallet and strap without a net is not, in their definition, a ULD.

Of course as the cargo industry developed and started carrying more and more cargo that was not necessarily suited to go underneath a cargo net such as a vehicle, a helicopter, other large items and particularly overhanging items, the use of straps without an accompanying cargo net became more commonplace. Furthermore as the use of floating pallets with the load tied directly to the floor of the aircraft grew in popularity, this also increased the usage of straps as primary restraint. But here is the kicker: not only was there no Minimum Performance Standard (MPS) for straps until just a few years ago, but also the application of straps to items of cargo requiring special restraint was left up to individual airlines to do as they saw fit, there were no industry standards, the strap manufacturers did not lay out how the strap was to be used, so it was pretty much up to the person on the spot.

Of course as the cargo industry developed and started carrying more and more cargo that was not necessarily suited to go underneath a cargo net such as a vehicle, a helicopter, other large items and particularly overhanging items, the use of straps without an accompanying cargo net became more commonplace. Furthermore as the use of floating pallets with the load tied directly to the floor of the aircraft grew in popularity, this also increased the usage of straps as primary restraint. But here is the kicker: not only was there no Minimum Performance Standard (MPS) for straps until just a few years ago, but also the application of straps to items of cargo requiring special restraint was left up to individual airlines to do as they saw fit, there were no industry standards, the strap manufacturers did not lay out how the strap was to be used, so it was pretty much up to the person on the spot.

Moving into 2016 this has all changed. First of all in 2011 the FAA published TSO C172 “Cargo Restraint Strap Assemblies”, creating for the first time a comprehensive MPS for straps of any type. The IATA ULD Panel responded to this initiative by establishing that from 1Jan 2016, only TSO approved straps should be used, and in the intervening period a large number of airlines have indeed transitioned away from non-certified straps to TSO C172 approved straps.

Moving into 2016 this has all changed. First of all in 2011 the FAA published TSO C172 “Cargo Restraint Strap Assemblies”, creating for the first time a comprehensive MPS for straps of any type. The IATA ULD Panel responded to this initiative by establishing that from 1Jan 2016, only TSO approved straps should be used, and in the intervening period a large number of airlines have indeed transitioned away from non-certified straps to TSO C172 approved straps.

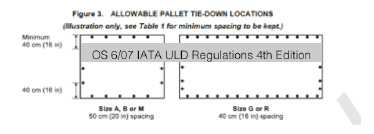

This in itself might have been relatively unremarkable but the investigation into the crash of National Air Cargo flight 102 highlighted once again that the use of straps was not following any kind of prescribed practices and that a great deal of practices could be unsafe. These findings have led to a significant amount of additional content in the revised FAA AC120 – 85A. Of particular relevance would be Section 2.8 Transport of Special Cargo and Section 3.3.3.2 Tie Down Strap Authorization. Furthermore the IATA ULDR section OS 6/07 has also been substantially updated, one very significant change being that unlike the good old days when straps could be attached anywhere and everywhere in the seat track around the periphery of the pallet there are now some very specific regulations regarding both positioning and spacing of cargo strap attachment points into a pallet, this requirement came about after testing showed that in the absence of such a requirement while the pallet itself was strong enough a concentration of cargo strap attachment points in a particular location could lead to overloading of the restraint latches in the aircraft Cargo Loading System and so enable the entire pallet to break loose under load.

What does this mean to the average cargo loading operation? Certainly first and foremost the days of guesswork are now gone, anyone putting even one finger onto a strap needs to know what they are doing and why they are doing it. In an attempt to provide some degree of clarity on this complex subject this article lists three key points:

- Restraint type- primary or secondary. A starting point for the use of any strap must be to determine if it is providing primary or secondary restraint. This is not as easy as it may sound, there are the obvious conditions such as a vehicle which will clearly be totally restrained by straps or a pallet loaded with general cargo containing perhaps a couple of heavier items which are individually restrained using straps but where the entire load is covered with an air cargo net. As always the problems lie with the grey areas in between the extremes, where perhaps for example a net is placed over a load and even some straps are being used underneath the net (making them secondary) but where one or two straps are placed externally to the net for some reason. In such a case the external straps do become primary restraint, subject to a completely different level of operational demands. The industry has been used to fairly haphazard application of straps until very recently and it is going to be quite challenging for them to adapt to these new much stricter definitions and regulations.

- Certification and condition status of any strap. As mentioned above, until not so many years ago, straps were not covered by any kind of certification by the aviation authorities and their MPS was purely as decided by the manufacturer. While generally straps would meet their stated maximum load requirement – generally 5000 lbs. – subtler aspects such as maximum elasticity and maximum slippage through the buckle during cyclic loading were not measured nor defined. TSO C172 has changed all that and straps carrying a TSO C172 marking now comply with a very well-defined set of performance standards. In line with these required standards straps also require far more attention to their condition than was ever evidenced in the past. For a strap to be used,it must not have any damage exceeding that specified by the manufacturer and contained on the ODLN, and given the focus on environmental degradation of textile items, straps must now be marked with a defined service life after which they must be withdrawn from service.

Application of tie down schemes. And then there is the whole manner in which straps are applied to the cargo itself and here again the good old days of making it up on the fly are gone. Wherever the primary restraint for the item of cargo will be by the use of straps, then the entire process of calculating the number and positioning of straps is required to be done by a person within the airline having specialist knowledge in this subject.

Application of tie down schemes. And then there is the whole manner in which straps are applied to the cargo itself and here again the good old days of making it up on the fly are gone. Wherever the primary restraint for the item of cargo will be by the use of straps, then the entire process of calculating the number and positioning of straps is required to be done by a person within the airline having specialist knowledge in this subject.

To sum up, the whole manner that the industry has applied straps in the air cargo loading process over the past 40 years is now up for review. Of course not everything needs to be thrown out, but what needs to come in is a radical overview of the knowledge requirements around the use of straps. This article has hopefully covered some of the key points and ULD CARE would certainly strongly recommend anyone in the industry who even remotely comes into contact with straps to take the time to read both the relevant sections of the IATA ULDR 4th Edition and also the FAA’s AC 120-85A. Of course as further developments in the use of straps arise, ULD CARE will be doing its best to keep our followers fully up-to-dat

Application of tie down schemes. And then there is the whole manner in which straps are applied to the cargo itself and here again the good old days of making it up on the fly are gone. Wherever the primary restraint for the item of cargo will be by the use of straps, then the entire process of calculating the number and positioning of straps is required to be done by a person within the airline having specialist knowledge in this subject.

Application of tie down schemes. And then there is the whole manner in which straps are applied to the cargo itself and here again the good old days of making it up on the fly are gone. Wherever the primary restraint for the item of cargo will be by the use of straps, then the entire process of calculating the number and positioning of straps is required to be done by a person within the airline having specialist knowledge in this subject.